Hey, franchise lovers! Check this out: Blogumnist and Hell House: The Awakening

- A new leading actor

- A sequel that’s a “prequel”

- Released four or more years after the previous sequel

- Ignored the franchise’s previous timeline or character arcs

- Incorporated a radically different tone

- Copied the plot of the original and pasted it in a new location

- Lack of involvement from original creative team

Being a horror and sci-fi fan, I've had more than my fair share of experience with sequels--the good, the bad, and the ugly. (After all, where would many horror and sci-fi icons and franchises be without lots and lots of sequels?) Of the list of sequel attributes that Dixon presents, I think that only two of them unmistakably qualify as "sins"--namely, ignoring the franchise’s previous timeline or character arcs and incorporating a radically different tone. Those two sins are hard to remedy, no matter what kind of creative team is at the helm, once they have been implemented into the production of a sequel.

The other five attributes are more of symptoms than sins, indicators that the sequel might be horrible but are by no means conclusive by themselves. For example, the sequels Dawn of the Dead

On the other hand, I think that there are two sequel sins that should be added to Dixon's list, sins that I've seen committed by movie studios way too often: the direct-to-video release of sequels (be it on VHS, DVD, or as a TV movie) and the lack of commitment to telling a sequel with meaningful plot advancement. Read on for more thoughts on the sinful thinking that had plagued horror and sci-fi franchises for decades.

To be clear, I happen to be a fan of the idea of movie sequels, if not always their execution. In the right hands and with the proper studio support, sequels allow filmmakers to further develop intriguing characters and explore provocative ideas that were introduced in movies that were originally produced as stand-alone stories. Sure, these kinds of sequels don't happen often enough and sometimes when they do, only fans of the original movie may recognize them as such while the overall critical consensus otherwise dismiss the said sequels as a mindless cash-ins. There have even been times where I've read reviews by critics who seemed deeply offended by sequels that required them to remember events and details from the first movie in order for the continuing story to make sense (curses to the sequels that make such unreasonable demands!).

Of course, Hollywood itself hasn't done much to encourage the positive, cynicism-free reception of sequels. Yes, they most often are quickie cash-ins, and they more often stem from a studio owning the rights to a movie and wanting to maximize their profits of such ownership than a genunie desire to continue a movie's narrative into a second or third movie. From what I understand of creative property rights, it's cheaper and more cost-effective for a studio to produce a sequel to something they already own and has proven its success than it is for them to invest in something completely new and unproven. Further complicating this problem has been the rise of the media mega-conglomerates over the last two decades. As FCC regulations of media ownership have relaxed, the concentration of media ownership has intensified while the diversity of media content has diminished.

Just about everything you read, watch or hear these days is owned by one of a small number of media conglomerates. Given the current trend of mega-megers between corporate giants, expect that number to get even smaller as the years go on and the strip-mining of their creative properties to continue. In light of this entertainment landscape, sequels, prequels, spin-offs and remakes are not signs of Hollywood running out of ideas; they are signs that Hollywood has become too cheap, bloated, single-minded and risk-averse to support new ones.

My personal complaints and overservations aside, here are my two additions to Dixon's sequel sins list:

The Direct-to-Video Sequel: Nothing says "we're just in it for the money" more than when a studio doesn't even bother to distribute to the megaplexes and goes straight to the video rental outlets and cable stations. These are usually low-budget affairs produced by no-name directors and actors and have nothing going for them other than a recognizable franchise name. I'm sure that some accountant can show you how straight-to-home-video sequels can generate respectable revenue, with an equation that looks something like this:

Tiny Production Budget - Limited Advertising x Lower Distribution Fee x Lower Audience Expectations = Profit!

To be fair, lower production budgets and lower audience expectations do allow for some creative experimentation that would otherwise be prohibited by the studios when they fund bigger-budgeted efforts. This is one of the reasons why I've enjoyed the two direct-to-video sequels to Guillermo Del Toro's Mimic

Commitment-Phobic Sequels: Say what you will about the Star Wars sequels

In comparison, there's more merit to this structured approach to sequel-making than there is to sequels that are produced solely on a studio executive's whim and with no creative planning involved. Lacking an overarching plan for a sequel or sequels to a franchise-worthy story not only results in poor storytelling, but it also dampens the excitement of the franchise's fans. It's hard for fans to care about a franchise when the studio that owns the franchise doesn't care either. Studios that hope to create franchises out of their movies really should be paying attention to Pixar, since their approach to the Toy Story sequels

A good story is a good story, whether it’s a completely original story or a continuation of story that wasn't originally intended to have a continuation. However, some situations are more supportive of creative storytelling than others. Perhaps the most troubling aspect about Dixon's list of sequel sins--as well as my two additional sequel sins--is not so much how bad they are for sequels, but how much they've been incorporated into the studio system as inherent parts of franchise building.

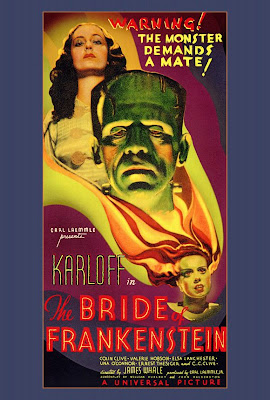

In closing, below are a few posters from some of Hollywood's earliest multi-sequel franchises--the classic Universal Studios monsters!

0 comments:

Post a Comment