Showing posts with label Grand Guignol. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Grand Guignol. Show all posts

Goodbye, Bay Harbor Butcher: A Look Back at Dexter (2006 - 2013)

Posted by Admin at 4:32 PM 0 commentsI remember reading a quote from Alfred Hitchcock a while back, although I can't find the exact source from where it originated. It was during an interview, and Hitchcock was asked about how to evoke an audience's sympathy for an anti-hero such as a criminal. He said that to have a sympathetic anti-hero, he can't just be what's normally thought of as a "bad guy"; he has to be the best at whatever vice he practices (e.g., bank robbery, art theft, high-profile assassinations, etc.) and, as long as he is portrayed by a handsome and charming actor, audiences will cheer the anti-hero along as long as he strives to maintain his reputation as the best. Hitchcock recognized that it's human nature to support hard work and success and his approach to anti-heroes proved that under the right circumstances, this support can be twisted around to cheer on theft, violence, excessive bloodshed, and death. Thus, while petty thieves, impoverished drug dealers and second-rate henchmen are the stuff of bit parts and small tragic dramas, expertly-trained assassins, international diamond thieves and rogue police officers who break all the rules to get the job done are romanticized and revered as superstars within the annals of pulp crime and suspense thrillers.

By that rationale, the TV series Dexter, which recently ended its eight season run on Showtime last weekend, gleefully pushed Hitchcock's approach to anti-heroes into the darkest and craziest corners of the horror genre. Charmingly played by Michael C. Hall, the titular character of Dexter Morgan built an audience of sympathetic viewers and impressed TV critics as he hacked and slashed his way through the criminal underbelly of Miami. Even though this plot summary sounds like the stuff of low-budget grindhouse horror, the creators of the series built enough twists into Dexter, his story and his supporting cast to make him approachable and even likable--likable enough that many fans were angered over how he didn't have a happily-ever-after ending, regardless of the fact that Dexter never stopped being a monster during the entirety of the series. Somewhere out there, Hitchcock is smiling from ear to ear.

Read on for my review of Dexter, and why I think that it's the boldest horror TV show to date. (Warning: There are many spoilers in this post.)

Dexter is a shamelessly manipulative show. Sure, it has plenty of plot contrivances to explain how Dexter gets both in and out of certain situations, but it is at its most manipulative in its central premise. The series begins with Dexter in his mid-thirties, which indicates that he's been successfully pulling the wool over Miami Metro Police Department's collective eyes for a very long time before the first episode begins. Furthermore, the show emphasizes Dexter's rigorous adherence to "The Code", a code of behavior that was taught to him by his adopted police officer Harry Morgan (James Remar), a code that stresses that only guilty people deserve to die. (Even though Harry is dead during the series, he appears frequently in the mind of Dexter to remind him of how important The Code is.)

By setting him up as a vigilante who "cleans up" the messes that the flawed legal system leaves behind (i.e., violent criminals who are obviously guilty but don't go to jail due to glitches in the system), Dexter does things that make him sympathetic in the eyes of viewers and even other characters within the show. Like any other serial killer, Dexter knows how to stalk human prey, set up portable "kill rooms", and successfully dispose of bodies; yet because he deliberately kills people who are a) guilty, b) let go by law enforcement due to technicalities, and c) cannot hurt anyone else after they die, audiences can appreciate Dexter's expertise in vigilante justice--even if Dexter's actions are motivated by a bloodlust for murder and not a desire for justice. (Think back to the character of Harry Tasker in True Lies: He's killed many people, "but they were all bad.")

Stories need to have an appealing lead character to build audience support; if the story is told in the form of a serialized TV narrative, then the audience support has to be maintained during the course of the series in order to keep the ratings high. To put Dexter into the context of Hitchcock's anti-hero type, Dexter Morgan's appeal at the beginning of the series largely stems from the fact that he's the best at what he does (e.g., he amassed a sizable body count while working for the Miami Metro Police Department but has neither been suspected nor caught in the act) and he produces outcomes with which most audiences would sympathize if not completely support. As with most TV dramas that center around a flawed lead character, audiences have come to expect the character to seek some sort of redemption as part of his or her development as the series progresses. In the case of Dexter, the show portrays Dexter as a man who was severely damaged psychologically at a very young age and is trying to grow into something more like a normal human being; since he is already the best serial killer he can be, the audience reaction (as Hitchcock anticipated) is to cheer him on in his efforts to become something more than that. But since Dexter is essentially a horror show about a man who is a monster that hides in plain sight, things aren't so simple.

Even though articles and critics have lumped it together with other dark, violent cable TV dramas such as The Sopranos and Breaking Bad, Dexter is a dramatic horror show and not a horrific drama series. I say this because of its close formulaic similarities to other horror TV series. Whether you're talking about Kolchak: The Night Stalker, The X-Files or Supernatural, the usual premise of a horror TV show involves characters balancing their lives between mundane, everyday reality and a parallel, coexisting reality that is populated by murderous, terrifying monsters. Dexter also bears similarities to horror shows such as Forever Knight, Angel and Moonlight where the protagonist is a monster who is looking for redemption by not killing innocent people and striving to become human.

The key differences between Dexter and other horror TV series are 1) all of the monsters are human (not a single extraterrestrial or paranormal entity in the bunch) and 2) not only is the lead character a monster, but he never stops being a monster and it's doubtful that he genuinely understands the difference between "being normal" and having a conscience. That's the running morbid joke behind Dexter Morgan: He frequently ponders the idea of what it means to be a regular human being--having a spouse and children, maintaining a job and close friendships, etc.--but in his eyes, being normal never completely equates to being sane.

Hitchcock's model of the anti-hero aside, I think that Dexter Morgan's antecedent is Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and the sizable horror subgenre of interpretations and reimagining that have followed it. Since the first season, I saw many similarities behind Dexter and Frankenstein's monster in that both were made to appear and behave human, but the flawed intentions and questionable methodology behind their creation inevitably leads to tragedy and death. In a sense, Dexter is the equal and opposite of Data, the android from Star Trek: The Next Generation. Star Trek and its spinoffs regularly used non-human characters to explore different aspects of what it means to be human; in the case of Data, he's an android who sees humanity as a standard to emulate and thus attempts to do things that humans would do (e.g., tell jokes, play music, go on dates, take care of a pet, have a child, etc.) but from a different, mechanical perspective. No matter how often he fails at being human due to his inherent limitations as a non-organic being, he continues to strive for human-ness and the Next Generation narrative regards his endeavor as a commendable one. Dexter also seeks to better understand what it means to be a normal human being, but he does so with the intent of finding better ways to accommodate his murderous tendencies; he's the serial killer who, as the saying goes, "wants to have it all". On the other hand, Dexter would have a kindred spirit in Cameron, the cyborg assassin from Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles. No matter how much both of these characters would like to appear and feel human, they can't get past the immutable fact that they were built (one literally, the other figuratively) to infiltrate groups of people and kill, kill, kill.

To follow the show's overarching logic, Dexter began violating The Code when he started to take a personal interest in the villains he hunts and aimed to incorporate aspects of his public life into his serial killer life in order to be a more complete human being. This began in the first season when he learned that the Ice Truck Killer (Christian Camargo) was his own biological brother, and then continued to spiral out of control in the subsequent seasons. In season 3, he created a killer in Miguel Prado (Jimmy Smits) when trying to find a close friend who could truly understand him; in season 4, his attempt to understand how to balance serial murder with family life by closely observing and directly interacting with the Trinity Killer (John Lithgow) wound up tearing Dexter's own family apart. With each attempt to improve himself through the interaction with other killers, more innocent people wound up dead--Doakes (Erik King), Ellen Wolf (Anne Ramsay), Rita (Julie Benz), LaGuerta (Lauren Vélez), and so on--and that is an unmistakable violation of The Code, even if these violations were not committed by Dexter's own hand.

The appearance in season 8 of Dr. Evelyn Vogel (Charlotte Rampling), the original creator of The Code, emphasizes the point that the series has been hinting at the entire time: that if Dexter had accepted his identity as a serial killer and behaved according to the stipulations of The Code, he could have spent the rest of his days as, as Vogel put it, "the perfect serial killer". Then again, by seeing how Dexter tried to change his modus operandi to become more normal during the series, it could be argued that the success of The Code was what led Dexter into thinking that he could eventually be something more than a serial killer of criminals. It's a very "meta" situation: a code of behavior that's designed to help an insane man remain free in a sane world also leads the man into believing that he can actually be sane while still doing insane things.

Each of these details surrounding Dexter ultimately led up to his grand epiphany in the final episode: to be truly human is to experience the need for redemption after committing horrible acts. Redemption only comes through a sense of remorse, remorse deep enough to spur meaningful and lasting acts of contrition. Dexter has felt guilt and regret from time to time, but none of those instances lasted. Take the recurring presence of Harry, for example: Even after learning that his adopted father committed suicide after witnessing the monster he created, Dexter still kept Harry as the spiritual face of The Code without a hint of remorse about his role in Harry's death. Perhaps his most misguided and twisted attempt at balancing normalcy and insanity happened after his sister Deb (Jennifer Carpenter) learned of his serial killing, and he did everything he could to get her to accept what he is. The end result left Deb an emotional and morally-compromised wreck, all so that Dexter could maintain a relationship with his sister without having to go to jail or be held accountable for his crimes in any way. His actions ultimately led up to his mercy killing of Deb in the hospital in the show's finale, although you could argue that he's been slowly killing Deb during the last two seasons anyway.

It may seem anti-climactic, but Dexter's realization in the last episode that he has never stopped being a monster to anyone, even the people who he believed he loved, is a significant and powerful conclusion to a show like Dexter. Unfortunately, for Dexter to finally understand the idea of remorse--no matter how briefly, and after eight gruesome seasons--was not fully grasped by everyone. As far as Salon's Daniel D'Addario is concerned, "[Dexter's] recent conclusion seemed plucked from the clear blue sky -- Dexter ran off to become a lumberjack, unpunished and abandoning his family." (To go back to the Frankenstein analogy, I think that the series ending with Dexter sailing out to sea into a hurricane with his dead sister Deb bears strong similarities to the ending of Shelley's novel, where the grieving monster drifts into the Arctic waters after seeing his creator's broken, dead body.)

Dexter isn't the perfect series. It had plenty of subplots that meander and go nowhere, as well as characters making decisions that strain credibility. I'm particularly disappointed that we didn't get to spend more time with Zach Hamilton (Sam Underwood), Dexter's "apprentice", and with Vogel. Even though it is indicated later that Vogel devised The Code for Dexter as a way of compensating for her own serial killer son Daniel (Darri Ingolfsson), it's also indicated that she spent at least 25 years experimenting with the idea of turning serial killers into "productive" members of society. I would have loved to have learned more about how her experiments and their underlying ideology evolved over time, as well as how many other Dexters she tried to create.

What Dexter did is difficult to accomplish, largely because most audiences and critics won't anticipate or understand what the show's creators and writers have done or why they did it in the first place. For example, as stated in the series finale recap by James Hibberd in Entertainment Weekly, "The past few seasons it's felt like the writers still think Dexter is a sympathetic hero whose needs are more important than any other character's despite the innocent people who have died along the way to support his addiction." No, the writers never thought that Dexter was a sympathetic character; they just applied Hitchcock's anti-hero philosophy to a very sinister scenario for eight seasons with high ratings, an avid fan base, and critical accolades. If that sounds crazy to you, it’s because it really is crazy--the cast and crew behind Dexter wouldn't had have it any other way.

Weekend Detention Becomes a Death Sentence in Bad Kids Go to Hell (2012)

Posted by Admin at 5:05 PM 0 commentsWhen a movie opens with a SWAT team bursting into a school library to find a teenager holding a bloody fire ax and surrounded by corpses--one of which being so fresh that it hasn't even collapsed to the floor yet--you know you're in for something different. Such is the case of Bad Kids Go to Hell, a 2012 movie that was directed and co-written by Matthew Spradlin. Spradlin based this movie on his best-selling graphic novel of the same name; however, because I haven't read the graphic novel yet, I can't say how faithful the movie is to its source material and which one is better.

After its jarring first scene, Bad Kids Go to Hell goes back eight hours to when six students at Crestview Academy, an upper-class private school, arrive for a day-long session of Saturday detention in their school's library. When one of them suddenly dies under suspicious circumstances, the other students begin to fear for their own lives. Is there a killer in their midst, or is something else afoot that's orchestrating their collective demise?

While I was watching Bad Kids Go to Hell, I had a tough time pinning down what kind of movie it wanted to be. It has plenty of horrific scenes and imagery, although it does not have the mood of a horror film; it doesn't take itself too seriously, but it's neither a comedy nor a horror film parody either. After seeing the final scenes, what I can say it that it is an extremely misanthropic and dark humored morality play. Many have viewed this film as a horror genre version of The Breakfast Club (1985), but its overtly sardonic attitude toward its story and characters puts it in the same class as another 80s teen movie, Heathers (1988).

What impressed me the most about this movie is its plot adheres to standard teen horror conventions, and then twists them around to the point where you’re not completely sure of what to expect. Like most teen horror films, the kids who are promiscuous, drink alcohol and do drugs wind up dead in one way or another; however, unlike most teen horror films that keep their characters and plots simple, Bad Kids Go to Hell provides plenty of background details (both explicit and subtle, and through dialog, flashbacks and visual cues) about how the characters connect to each other and the school's own sinister history, and how these relationships set the stage for what happens during Saturday detention. Watching Bad Kids Go to Hell is like watching an elaborate, Rube Goldberg story configuration click together sequentially, plot point by plot point, to deliver a gleefully pitch-black ending. Sure, some of the subplots feel unnecessarily convoluted and not all of the jokes hit their marks, but rarely have I ever seen such an elaborate contraption in the service of such morbid and cynical humor. When I say that this film is cynical, I cannot stress it enough; in fact, even though it looks and feels like a teen movie, this film is so cynical that I doubt most teens would fully understand or appreciate what it is trying to do.

Bad Kids Go to Hell isn't a flawless film; I've seen better blends of horror and comedy than this one, and it's not nearly as ambitious or insane as another recent offbeat teen film, Detention (2012). Then again, I love grim-humored satire that proudly wears its cynicism on its sleeve, so I enjoyed watching this movie even if it doesn't completely work. If you like that kind of humor too, then you should give Bad Kids Go to Hell a look.

Bon Appétit: A Season One Review of NBC’s Hannibal

Posted by Admin at 4:41 PM 0 commentsThis review may be a bit late--the season finale of Hannibal aired last week--but I’m going to do this anyway. It’s not often when a horror TV show succeeds in being consistently creepy during an entire season, and Hannibal does so with flying, blood-spattered colors. It also breathes disturbing new life into the character of Dr. Hannibal Lecter, which is an impressive feat unto itself. Connections to Thomas Harris’ horror novels aside, Hannibal is what TV shows like The Following and Criminal Minds should be, and what earlier shows such as Millennium and Profiler could have been.

Instead of treating serial killers as monster-of-the-week antagonists who are quickly foiled at the end of each episode, Hannibal uses its main characters--namely Hannibal Lecter (Mads Mikkelsen) and Will Graham (Hugh Dancy)--to explore serial murder and the nature of identity and insanity on a more complex and nuanced level. In doing so, the series depicts Lecter in a manner similar to Dexter Morgan (Michael C. Hall) in Dexter and Jim Profit (Adrian Pasdar) in Profit. These are depictions of murderous protagonists who go about their lives across days, weeks and months, allowing audiences to observe how such insanity can remain undetected (or at least unproven, from a legal perspective) by the killers’ peers in what would otherwise appear to be mundane settings and situations. There are no quick resolutions or sudden revelations in Hannibal; each murder and subsequent investigation leads to more murders and investigations, with the characters unaware of the central evil that ties it all together. It’s unnerving stuff.

As the series’ creator, executive producer and occasional script writer, Bryan Fuller has done an amazing job at bringing Harris’ stories to life on the small screen. Even though the 1991 film adaptation of The Silence of the Lambs popularized Hannibal Lecter among a wide audience, I think that Fuller’s Hannibal, which is mostly based on characters and situations from the 1981 novel Red Dragon, is the most intriguing and disturbing adaptation of Harris’ work. Not only do the scripts create a vivid, multi-layered world of characters, but the show’s direction maintains a grim, foreboding mood across the entire season, so much so that it almost feels like an ongoing miniseries instead of a sequence of individually produced episodes.

For as strong as the cast of Hannibal is, the series would have fallen apart without its two leads, Mikkelsen and Dancy. Mikkelsen’s interpretation of Lecter is a chilling one, without an ounce of camp that came to be associated with the character in his silver screen outings. Mikkelsen combines an outward appearance of resolute sanity and cultural sophistication with an aura of icy aloofness, making this version of Lecter impossible to completely understand and predict. Dancy provides the dramatic counterpoint to Mikkelsen’s Lecter, infusing the character of Will Graham with a burgeoning emotional imbalance that’s the side effect of his ability to “see” murders through the eyes of the serial killers who commit them. The cat-and-mouse game between Graham and Lecter is largely subliminal for most of the season, and Mikkelsen and Dancy’s performances keep it moving along with the right amounts of tension and symmetry until the season’s intense finale.

For as gruesome as it can be (a totem pole made from human body parts, murder victims transformed into musical instruments, etc.), I’m still surprised that Hannibal is on NBC and not on Showtime or some other cable channel. Regardless, I’m glad this show is on at all and will be coming back for a second season next year. This is what horror television should be, and I can’t wait to see where it goes next.

Who's up for a game of Jenga?

The Following Season One Review

Posted by Admin at 5:27 PM 0 commentsIt's over--for now. The Following, Fox's attempt at the kind of serialized horror that has proven to be successful on cable TV with shows such as Dexter, The Walking Dead and American Horror Story, wrapped up its first 15 episode season last Monday. I love horror, so I can't fault a major network for trying to bring new horror TV shows to prime time. However, after a strong start, a great cast and some intriguing ideas, The Following sputtered to the end of its initial run with a lot of sound and fury that signified very little. Read on for my complete review of this show's freshman season.

For those of you who haven't seen The Following yet, it's about a college literature professor-turned-serial killer Joe Carroll (James Purefoy) and the FBI agent who caught him, Ryan Hardy (Kevin Bacon). The series begins with Carroll escaping from prison and the FBI bringing Hardy in to capture him again. Yet after Carroll is brought back into custody, Hardy and the FBI discover that Carroll has been using his years in prison to build a cult of devoted followers from around the country to do his bidding. The cult is rooted in Carroll's twisted interpretations of the writings of Edgar Allen Poe, and its members are determined to carry out a sinister master plan that involves Hardy and Carroll's ex-wife, Dr. Claire Matthews (Natalie Zea).

The biggest problem I have with The Following is how thinly developed the main villain and his cult of minions are. There were times when the show's premise--a serial killer and his followers committing murders based on classic literature--reminded me of the excellent Vincent Price film, Theatre of Blood (1973). In that film, Price played Edward Lionheart, a deranged Shakespearean actor who leads a troupe of follow lunatics on a killing spree of critics who he believes destroyed his career and each murder is based on a scenario from Shakespeare's plays. The significant difference, though, is that while Theatre of Blood made ample usage of Shakespeare and British theatre culture as part of its plot, The Following doesn't really know what to do with Edgar Allen Poe and the macabre literary tradition that he followed.

Sure, many episodes referenced some of Poe's more popular works and they even had cult members running around in rubber Poe masks, but what exactly draws Carroll and his followers to Poe's work enough to make it the basis of a murderous cult ideology is never explored in any significant depth. It felt like Williamson believed that frequently name-dropping a horror icon such as Poe in his series would make The Following scarier by extension. It didn't, and it instead revealed how much Williamson doesn't understand about Poe specifically and Gothic horror in general.

Williamson's inability to convincingly portray the obsession that Carroll and his cult have with Poe led to other problems throughout the series. Without developing the Poe-centric ideology of the cult, the cult itself never materializes as a distinct presence within the show. If anything, the cult becomes an excuse to show characters doing violent and crazy things at key, plot-driven moments; yet because the characters in question lack any discernible motivation, all they are good for is an occasional jump scare and nothing more. Furthermore, without a core ideology, Carroll's supposed plan for his cult never comes to fruition--largely because Carroll's behavior and decisions during the second half of the season cast considerable doubt on whether he had any plan in the first place. Indeed, the version of Carroll we see at the end of the season seems much more like a hack writer and vengeful lover than a criminally brilliant, serial killing cult leader.

(Don't take it too hard, Professor Carroll. I can think of a few Cylons who can sympathize with the desire to kill lots of people but are also unable to devise a good master plan that will make the most out of such murderous desires.)

We were supposed to have a plan too, dammit!

Looking back, it felt like there were two conflicting plots in The Following: One is about a serial killer who uses his psychological manipulations of an FBI agent as the basis of a novel, and the other is about a serial killer who develops a cult of killers-in-training on an estate within a gated upper-class community. In the hands of a talented writer and production team, either of these plots could have been the basis for genuinely terrifying television entertainment. Yet in the hands of Williamson, neither of these plots--which share the common character in Carroll--amount to much, which leaves viewers with a horror TV series that alternates between a prolonged cat-and-mouse chase between FBI agents and assorted killers and scenes between cult members that play out like some kind of soap opera populated by attractive crazy people. Such a series does have a fair amount of strange, creepy moments, but it doesn't make for memorable TV either.

I've heard that The Following has been renewed for a second season, so I'm hoping that this show will improve when it returns. Yet if Williamson is content for his show to be nothing more than 24 with serial killers--which is what seems to be the case so far--then The Following will never become a distinct horror show of its own.

Giallo and Slasher Fans Get a Prime Time Treat in The Following

Posted by Admin at 2:28 PM 0 commentsI finally got around to watching the first episode of The Following, Fox's latest horror TV series. While there are other horror shows on other non-premium networks, shows such as Supernatural and American Horror Story, The Following is the only one that is firmly rooted in the giallo/slasher subgenre of horror. As a passionate fan of that subgenre, I'm grateful for this show's arrival. Not only is it off to a promising start with an interesting premise, but I don't have to pay extra on my cable bill to watch it (as opposed to subscribing to Showtime to watch another serialized giallo/slasher series, Dexter).

The Following is the brainchild of Kevin Williamson, whose previous horror credits include TV series such as The Vampire Diaries and movies such as I Know What You Did Last Summer and three of the four Scream movies. The show begins with FBI agent Ryan Hardy (Kevin Bacon) coming out of retirement to help catch serial killer Dr. Joe Carroll (James Purefoy) who recently escaped from prison. The first episode looks and feels like other well-known serial killer movies--particularly Manhunter and Se7en--but as the episode progresses, it becomes clearer that Carroll has an army of devoted serial killers in training to help him accomplish a much grander, gorier plan that what was originally suspected.

The first season of The Following will consist of 14 episodes broadcast during 14 consecutive weeks, in order to give the show a serialized "page turner" kind of feel. So far, it's working--the first episode ends on a cliffhanger, and I suspect each episode will up until the very end. I can't wait to see where this show goes next. Some additional thoughts:

* The Following wouldn't be the first serialized giallo/slasher series to appear on TV. There were also Harper's Island, which aired on CBS in 2009, and Epitafios, which aired in Argentina in 2004.

* When the first episode of The Following aired last Monday, it was immediately preceded by an episode of Bones that featured a recurring serial killer villain, the elusive Christopher Pelant (Andrew Leeds). The episode, which was titled "The Corpse on the Canopy", began with a flayed, jawless corpse found suspended over a canopied bed and ended with a character sowing his own face together after being shot in the head. Nice thematic pairing there, Fox.

* In a subplot reminiscent of last year's movie The Raven, Carroll patterns his killings and murderous philosophy after the literary works of Edgar Allen Poe. I'm personally hoping that if this series gets another season, the focus will shift to a Carroll disciple who patterns his or her killings after the work of Japan's answer to Poe, Edogawa Rampo.

* The overall plot of The Following--a serial killer who forms a cult that carries out his bloodthirsty wishes--sounds like something that would've fit perfectly within the first season of Millennium, another horror series that aired on Fox from 1996 to 1999. While I think that The Following will fare better than its predecessor due to its serialized format--Millennium suffered quite an identity crisis during its three season run--both series have been considered controversial due to their excessive violence on prime time network television. Millennium was even the subject of an advertiser boycott campaign during its first season.

Experiments in Unorthodox Horror: House (1977) and Detention (2012)

Posted by Admin at 4:12 PM 0 commentsWhen crafting a horror film, directors use a variety of cinematic tropes to convey to the audience that the story they are watching belongs in the horror genre. Sometimes, the director may choose to get under the viewer's skin by keeping the source of terror off screen and only hinting at it through narrative hints and suggestive sound effects and camera angles. In other situations, the director may opt for graphic depictions of explicit violence and gore--either in brief and sudden bursts or repeatedly throughout the story--to keep the viewer anxious and off balance. But what happens when a director foregoes the mood-building techniques that are often associated with horror movies and chooses instead to utilize tropes from other genres to tell a story of dismemberment, death and despair?

Two examples of off-kilter horror can be found in Nobuhiko Ohbayashi's House (1977) and Joseph Kahn's Detention (2012). Even though these films are three decades apart, they both are coming-of-age horror films that are difficult to describe due to their unpredictable, illogical selection of counter-intuitive cinematic styles as a key part of their storytelling process. House is a dark fairy tale that's told in a psychedelic, stream-of-consciousness succession of images and moods, while Detention is self-referential teenage comedy/drama that's vigorously mashed together with time travel sci-fi, body horror and slasher film archetypes. Both films could have been scripted and shot as conventional horror movies, but the fact that they weren't makes them fascinating films to watching in their own right. Read on for my complete comparison.

House tells the story of Oshare (Kimiko Ikegami), a teenage schoolgirl who is looking forward to spending her summer vacation with her widowed father (Saho Sasazawa). Yet when she learns that her father's new girlfriend Ryoko (Haruko Wanibuchi) will be going with them on vacation, she decides to visit her aunt (Yoko Minamida) and brings several of her teenage friends along with her. When the girls start disappearing in the aunt's house, the surviving girls struggle to survive by fending off a slew of demonic, supernatural attacks, including a few from possessed furniture.

House is a hard movie to pin down in terms of what it's supposed to be. It's filled with horrific images, but it's not exactly a horror movie; it's campy and absurd, but it's not a comedy. It's frequently childish and immature, with scenes that could easily be inserted into a live-action TV show for kids, and yet it's not a film for children (at least by American standards). These observations may make House sound like an absolute mess of a film to watch, but it's not. In fact, I think that Ohbayashi's approach to how he filmed the script for House allows him to tell and haunting story of when adolescent idealism and naïveté collides with--and is annihilated by--the pain, possessiveness and sensuality of adulthood.

The movie focuses on Oshare and her friends, a group of teenagers who are reaching the end of their educational years. Each girl has a simple nickname that summarizes her personality: "Prof" is the nickname of the smart girl, "Melody" is the nickname of the girl who plays the piano, "Sweet" is the nickname of the girl who always does what she can to help, and so on. The characters' childlike approach to life is reflected in the movie's visual style: all of the settings are very stylized and obviously artificial. This idealized world runs amuck when the girls are attacked one by one at the aunt's house, as if their immature view of the world is turning against them as adulthood (as represented by the aunt, her past and her expansive house) exerts control over their lives. Essentially, House depicts the transition between childhood to adulthood as a sort of death that is traumatic, ghastly and inescapable in equal measures.

Curiously, House utilizes nudity as part of its grim depiction of growing up, although not in the way that most American audiences would expect. For example, nudity in slasher films usually happens in the context of teenagers having sex before they are inevitably murdered by a psychotic killer. In contrast, the nudity in House happens shortly before, during and/or after the girls' deaths--not as part of any sex act, but as if it was an inevitable component of dying. In a sense, the act of dying in a gory manner in House eroticizes the girls, reflecting their transition into sexual maturity and adulthood and the gruesome "death" of their pre-adulthood lives. Adding considerable unease to these death scenes is how some of the girls giggle with glee over their new status as unclothed and dismembered corpses.

Detention doesn't have the same thematic depth as House, but it still knows how to tell as coherent story in what otherwise appears to be a calamitous mixture of incongruous styles. Detention focuses on Riley (Shanley Caswell) as she struggles her way through high school in Grizzly Lake, a town that has been experiencing a rash of UFO sightings. Riley wants to ask Clapton (Josh Hutcherson) to the prom, but her wishes are complicated by her inexplicably spiteful best friend Ione (Spencer Locke), her amorous guy pal Sander (Aaron David Johnson), and a masked serial killer named "Cinderhella" who has been murdering students and has targeted Riley as his next victim. At times, Detention reminded me of Scream, Donnie Darko and a few episodes from the first three seasons of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and yet it’s nothing like those titles.

While Detention bears similarities to the storytelling approach used by House, these films differ considerably in terms of how they view the relationship between adolescence and adulthood. Whereas House views the transition of adolescence to adulthood as a fixed point that can only be passed once in a lifetime, Detention takes a much more fluid approach by showing how the two age groups occasionally overlap. Part of this could reflect how the mainstream cultures of Japan and the US differ in their views of adolescence and adulthood, but I also think that this might have something to do with when both films were made. Ohbayashi's wild visual style reflects the incongruity between how adolescents view of the world and how adults live in the world; in contrast, Kahn's wild visual style emphasizes how incongruity dominates modern teenage life.

The movie world of Detention--where time travel, masked killers, human-insect hybrids and flying saucers coexist in a sort of mundane way in the halls of a high school--is a thematic parallel to the omnipresent information overload that real teenagers are bombarded with through the Internet, cell phones, computers, and high-definition, multi-channel media. One of Detention's subplots features a student who becomes the most popular student in school after travelling back to 1992, with the rationale that a digital-media-saturated teenager from 2012 is much more savvy and cooler than an analog-media-saturated teenager from the early 90s. The movie may lack the pervasive fatalism of House, but it pulls off a very impressive feat by telling a complete and satisfying story from a selection of disparate characters, situations, themes and styles--much like our fragmented-yet-interconnected electronic world, a world that even adults cannot escape. If Detention has any underlying metaphorical message, it is that if teenagers can make sense of and survive our current digital age, then there may be hope for us in the future after all.

Horror films like House and Detention are not for everyone. These films are more like frantic, feverish dreams than traditional narratives that feature well-defined, easily-understood plots and firmly established moods. But if you're willing to try something that's much different than what you normally expect from a horror movie or a horror-comedy, then House and Detention make for an unforgettable double feature.

Flip Top Box: A Song About Necrophilia from the 50s

Posted by Admin at 4:46 PM 0 commentsDid you ever remember loving something from your early childhood only to realize when you're much older that the object of your prepubescent affection wasn't what you originally thought it was? If so, I've got a story for you.

Way back when before I was in kindergarten, my sister and I would listen to some 45 rpm records (give yourself points if you know what a 45 rpm record is) that our mom bought when she was a teenager. One of these records that I used to play repeatedly--usually when my buddies from down the block came over--was called "Nee Nee Na Na Na Nu Nu" by Dicky Doo And The Don'ts. As you can tell just by the title, it is a very silly song that easily amused pre-kindergarten kids like us. You can listen to it here:

There was another song on the other side of the 45 that I would also listen to once in a while, but I didn't understand what it meant so I didn't play it often. It was called "Flip Top Box", and I had no idea what the lyrics were talking about so it didn't hold my interest. Leave it to my memory and curiosity to get the better of me, and I recently decided to look up the lyrics to the song to understand what it really meant. You can read the lyrics here.

From what I have read elsewhere, rock songs about monsters and morbid subject matter were written and performed long before the arrival of heavy metal music and "Flip Top Box" is certainly one of the more ghoulish tunes from its time. Indeed, a love song about a man who is buried in a coffin with an easily removable lid so that his girlfriend can dig him up later for some "hugging and a-kissing" is a love song that's not meant for beating hearts. Listen for yourself:

Nerd Rant: Somewhere Out There, a Comic Book Supervillain is Missing His Face

Posted by Admin at 2:20 PM 0 commentsI don't read monthly comic book series anymore. They're too expensive for my budget these days, so I have reduced my comic book intake to stand-alone graphic novels and multi-issue compilations. I stay informed of what DC and Marvel are doing through comic book reviews and news updates, so I'm sure you can imagine my surprise when I found out that the Joker had his face cut off at his own request a few months ago. Yes, really:

Can you read this J-J-J-Joker Face?

I heard about this plot development a while back but I didn't pay much attention to it because of the other stuff that DC had been doing at the time with its company-wide reboot of all of its characters and their respective comic series. Batman series writer Scott Snyder has been touring the news outlets as of late to promote his upcoming story arc involving the Joker called "Death of the Family", which will begin in October. As part of this arc, Joker will be sporting a new look à la Leatherface, with his removed face attached to his head as a sort of mask.

This wouldn't be the first time that Batman has dipped his toes into giallo/slasher territory. Even though their origins pre-date Italy's golden years of giallo and America's slasher movie craze of the 80s, Batman villains such as Two-Face, Mr. Freeze and Scarecrow have backgrounds that are very similar to giallo/slasher villains. In fact, Snyder's recent Batman arc, "Night of the Owls", was clearly influenced by the giallo/slasher subgenre of horror, from the masks worn by the killers to the dramatic unmasking of one of the key villains. Read on for more thoughts about the Dark Knight's repeated flirtations with horror and how they never go anywhere in the long run.

The "Night of the Owls" arc and the faceless Joker come on the heels of four new additions to Batman's rogues’ gallery: Professor Pyg, The Absence, Flamingo, and the Dollmaker. Here are some tidbits about each of these villains, courtesy of Wikipedia and the Batman Wiki:

* "Professor Pyg has an obsession with making people "perfect", which he accomplishes by transforming them into Dollotrons, a process that bonds false "doll" faces to their own, presumably permanently. Professor Pyg uses cordless drills, hammers and ice picks along with the "doll" faces in the process of converting his victims into Dollotrons. It appears the operation he performs involves brain surgery or a form of lobotomization and possible gender realignment."

* The Absence is one of Bruce Wayne's former girlfriends. After surviving a gunshot wound to her head (which has left a permanent hole through her cranium--seriously), she stalks and kills Bruce's other former mistresses.

* "Flamingo is a psychotic hitman. He was lobotomized by the mob and was recruited by them. Despite his name, as well as his pink uniform and vehicles, he is a sociopathic, mindless, killing machine, nicknamed "the eater of faces", a title he has lived up to."

* The Dollmaker is a "Gotham City Serial Killer who creates "dolls" out of the skin and limbs of his victims. ... His mask is partially made of skin from this deceased father." The Dollmaker also has a "family" consisting of disfigured, sewn-together minions. The Dollmaker was also the same character who removed the Joker's face (a face that I'm assuming that the Flamingo will not eat).

As a horror fan, I love when superhero comics feature story lines that are strongly influenced by pulp horror; thus, I would really like to believe that the Batman comic book series will finally commit to becoming a horror comic. Heck, with new villains like this, now would be a perfect time to put Batman in a crossover miniseries with the characters from Hack/Slash.

Yet in light of previous attempts by DC to make Batman "grittier" (read my previous posts about Batman's so-called grittiness here and here), I'm certain that all of these new characters and the now faceless Joker are just more gimmicky and forgettable look-at-how-insane-Gotham-City-has-become-THIS-time stories, something that DC has been trotting out regularly in its Batman titles since The Dark Knight Returns and The Killing Joke during the 80s.

No matter how psychotic and grisly Batman's villains get, the status quo in Gotham City will never change in any significant way (just ask Jason Todd). Such predictability makes DC's attempts at providing grindhouse-style shock and gore through its most popular superhero character feel anticlimactic and feeble. If DC really wanted to be edgy, it would add figures such as Removable-Face Joker, Face-Eating Flamingo, Disfigured Dollotrons, and a Mix-and-Match Dollmaker Family to Fisher-Price's Imaginex DC Super Friends toy line for the ages 3 to 8 demographic.

Look--here's a Fisher-Price Batman play set with a Bane action figure. So where are

the Broken Back Batman and Paralyzed Bruce Wayne (with Wheelchair) action figures?

Nerd Rant: Someone Actually Paid $70 Million to Make a Film Called Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter

Posted by Admin at 4:44 PM 0 commentsI've seen a lot of things at the movies. Gory things, offensive things, full-frontal things, and so forth. Some were great, some were good, some were average, and some were very, very bad. Yet of all the things that Hollywood has put into the movie theaters lately (as opposed to the wild and woolly world of direct-to-video), last weekend's Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter leaves me speechless. During the same summer as Battleship, a movie based on a board game, and it's this film that leaves me speechless. I thought that the humorless The Raven from last April that featured Edgar Allen Poe as an amateur detective was bad enough, but now we get the 16th President of the United States as a dour vampire slayer.

Come on, Hollywood! You've got a film about an axe-wielding president who kills monsters and this is the best that you can do? What, did the $70 million budget give you cold feet so you decided to play it serious for fear that a campy horror film would alienate or anger viewers? Did you get so high on CGI that the resulting digital haze made you forget how ridiculous this whole idea is? We live in a time where a toy series called "Presidential Monsters" is making its rounds among the horror collectibles crowd and yet you couldn't bother to include some inspired, morbid mayhem to salvage your misguided mash-up of historical drama and creature feature?

Yes, this action figure really does exist. Yes, a Lincolnstein movie would be

much more entertaining than Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter.

I think they should've cast Hugh Jackman as Abe and rewritten the script into a movie musical, where Abe could sing and behead vampires while swinging his axe in rhythm with the tunes. Imagine Abe slaughtering the bloodsucking undead while singing the Gettysburg Address; what could be cooler than that? Throw in roles for other stage theater-inclined X-Men movie vets for name recognition purposes (e.g., James Marsden, Ian McKellen, Patrick Stewart, etc.) and change the title to something more outrageous--say, Honest Abe vs. Dracula--and this could've been a b-movie blockbuster smash.

A 19th century historical figure that fights vampires?

Been there, done that, and on a cheaper budget too.

There is so much wasted potential in Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. I guess we'll just have to wait until September for FDR: American Badass!, which stars Barry Bostwick as FDR, Ray Wise as General MacArthur, and Kevin Sorbo as Abe Lincoln. Yes, really.

Here's Abe clobbering the cyborg version of John Wilkes Booth (a.k.a. "John Wilkes Doom")

during a time travel team-up with the Dark Knight on Batman: Brave and the Bold.

The Weird World of Eerie Publications Book Review: Reviving the Horror Comic Book Through Recycling

Posted by Admin at 1:36 PM 0 commentsOf all the media formats that have distributed the horror genre to the masses, few have had it more difficult than the comic book. Congressional hearings that were held during the mid-50s based on nothing more than a fleeting fit of public hysteria caused horror comic books to suddenly vanish from newsstands everywhere and dealt a crippling blow to the comic book industry in general. The horror comic eventually came back during the 60s and 70s, with DC, Marvel and Warren Publishing contributing titles that would help this format recover. The most notorious contributor to the horror comic revival was Eerie Publications, which is the central topic of Mike Howlett's engaging and informative book, The Weird World of Eerie Publications: Comic Gore That Warped Millions of Young Minds.

Howlett's approach to the history of Eerie Publications and its contributions to the horror comic format is exhaustive, almost to a fault. Howlett obviously loves the work of Eerie Publications and you'll finish the book with the conviction that he could tell you anything and everything about that company at a moments' notice. Yet even if you only have a passing familiarity with horror comics and the titles produced by Eerie Publications, Howlett's book is worth purchasing for a snapshot of what pulp horror publishing was like during the 60s and 70s. Curiously, Weird World also indirectly highlights the conspicuous similarities between low-budget horror comic publishing and low-budget exploitation horror filmmaking. Read on for my complete review.

The ideal companion text for Howlett's book is Jim Trombetta's The Horror! The Horror!: Comic Books the Government Didn't Want You to Read!. (Read my review of that book here.) Trombetta's book covers the rise and fall of the horror comic during the early 50s, and Howlett covers the revival of the horror comic during the 60s and 70s (albeit from the perspective of Eerie Publications). Reading these books together will give horror fans a more complete picture of horror comic history and how the horror comic format was forced to change due to cultural and political events and changes in public media consumption and in the publishing industry. Where the books differ is in terms of approach: While Trombetta's book largely explores the recurring themes and imagery in horror comics from the 50s, Howlett devotes his book to the history of Eerie Publications and its artwork, artists, publication staff and newsstand competitors.

The story told about Eerie Publication's horror comics as told in Weird World largely revolves around two individuals: publisher Myron Fass and editor Carl Burgos. Fass specialized in the publication of low-budget pulp magazines, and Howlett's book reviews the full range of trashy and unscrupulous magazines that Fass produced in addition to Eerie Publications' horror comics. In following his preference for material that's cheap and quick to produce, Fass published multiple horror comic titles (Horror Tales, Terror Tales, Tales from the Tomb, etc.) by re-publishing horror comic stories from the original golden age of horror comics during the early 50s. Burgos, a veteran comic book artist, oversaw the production of the Eerie Publications' titles. Before working for Fass, Burgos' most noteworthy accomplishment was his creation of the Human Torch character during the 1940s. When Marvel Comics revived the character for its Fantastic Four series in 1961, Burgos received no compensation from Marvel for his creation; his falling out with Marvel estranged him from the mainstream comic book industry, which led to his editor role at Eerie.

Howlett details how Fass and Burgos could get away with publishing multiple horror comic titles by mostly recycling horror comic stories that were already published back in the 50s. Eerie Publications would release some completely new material from time to time, but rehashing old material was Fass and Burgos' dominant method of publication. However, instead of just republishing the original stories, Fass and Burgos would hand the stories over to artists who would re-draw and re-script the stories with varying degrees of faithfulness to the source material. Some revisions were similar to the original stories, while others would take the stories in completely new directions. Either way, the new versions of the stories were always much gorier and more sexualized than the originals. Some stories would be republished up to three or four times; all Fass and Burgos did was hand an old story to a new artist and provide a new title, and thus the story could be regarded as "new". Even the cover art was recycled over and over again with minor variations. (Click here to see a gallery of Eerie comic cover comparisons that I assembled in a previous post.)

While I was reading Howlett's book, two things came to mind:

* Eerie's method of repeatedly recycling creative content and adding lots of gore and sex to each reiteration is almost symmetrical to how low-budget horror films were made during the 50s, 60s and 70s. Cheap horror films frequently recycled plots, props and footage from other movies, in addition to using stock footage and background music to pad thin production budgets. During the 60s and 70s, the grindhouse conventions of sexual titillation and increasingly detailed gore effects were used by low-budget filmmakers to promote their otherwise obscure horror films.

* If anything, the revival of the horror comic book proved exactly how hollow the 50s Congressional hearings and the subsequent Comics Code Authority (CCA) really were. In the case of Eerie Publications, it not only republished the very same stories that Congress set out to ban, but it also made them gorier and sexier than their original versions. Furthermore, Eerie couldn't be restricted by the CCA because it called its publications "magazines" and not "comics" and thus was not subject to CCA oversight.

The only problem I had with Weird World is its occasional excess of minutiae. I understand how Howlett wanted to ensure that everyone who was involved in Eerie Publications got their due, but there were times in the book when I was struggling to keep up with who's who outside of Fass and Burgos. Yet this complaint is minor, because the book offers so much information and artwork that horror fans are sure to enjoy. I highly recommend The Weird World of Eerie Publications for both horror and comic book fans who are interested in learning more about the horror genre and its relationship with the comic book industry during the 60s and 70s.

The Brief History of 50s Horror Comics Exposed in The Horror! The Horror!: Comic Books the Government Didn't Want You to Read!

Posted by Admin at 3:42 PM 0 commentsWhen I think of horror and sci-fi stuff from the 1950s, three things immediately come to mind: the rise of the "atomic mutant" subgenre of horror/sci-fi movies, the popularity of alien invasion stories, and Hammer Studio's early ventures into horror cinema. On the other hand, I never thought much about horror comics from that era. I knew that there were Senate hearings about the content of comic books in 1954, and that these hearings were prompted by the publication of Seduction of the Innocent, a book by psychiatrist Fredric Wertham. In his book, Wertham accused comic books of inciting juvenile delinquency on an epidemic level. By the end of the hearings, the comic book industry implemented a self-regulating Comics Code Authority (CCA) just so it could stay in business.

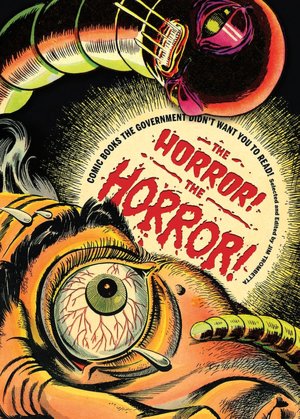

Fans of superhero comics (myself included) are well-versed in how the CCA Code sanitized the content of DC's superhero universe, and how also it set the stage for Marvel to introduce a new generation of innovative-yet-CCA-compliant superheroes. Yet in comparison to other genres, horror comics vanished from newsstands overnight because of the CCA. In his book The Horror! The Horror!: Comic Books the Government Didn't Want You to Read!, author Jim Trombetta recounts the hysteria surrounding horror comics during the mid-50s and the people who were involved--the critics, the publishers, and the artists. He also reprints many examples of artwork from these controversial comics, which he uses to critically analyze the comics' recurring imagery and themes. Click below to read my complete book review, and why Trombetta's work is a great addition to the short lists of books that chronicle the most successful act of government-sponsored censorship in the US.

Trombetta begins his book with an overview of the Senate hearings and the hysteria that led up to the hearings, with subsequent chapters devoted to particular aspects of 50s era horror comics (skeletons, sexuality, shrunken heads, race, etc.). Each chapter is separated by pages of reprinted artwork from the comics themselves, including covers, panels and a few complete stories. In one of the initial chapters, Trombetta succinctly describes the reasoning that drove the censorship of horror comics: "(I)n April 1954, comics became the first pop-art medium to be regulated nearly out of existence by the government. ... It was, in true Orwellian fashion, as if the government thought that bad things would vanish if they couldn't be read or thought aloud." Given how comic books have been repeatedly derided by cultural elites as "junk" entertainment, it's astonishing to read Trombetta's account of how influential members of our own government willingly believed that horror comics could do so much harm to society and that banishing them to the point of complete cancellation would ultimately serve the greater good.

What I enjoyed about The Horror! is how Trombetta analyzes horror comics and the fears and insecurities they reflected at the time. Early horror comics feature many of the same ideas and images that many other forms of horror storytelling have, but Trombetta keeps his scrutiny of them rooted in the popular culture of the late 40s and early 50s to give readers a better frame of reference for understanding. To that end, he notices certain overlaps between the horror comics with the then-contemporary war comics and "true crime" comics.

Further contextualizing the horror comics is the inclusion of an episode of Confidential File, which is on a DVD inserted in the book's rear flap. Confidential File was a news magazine show that ran from 1953-58 and was hosted by LA Times reporter Paul Coates; the episode on the DVD shows Coates "investigating" horror comics. If you think that news in our current era of 24-hour cable- and Internet-driven coverage is nothing but empty sensationalism, then you need to see this episode. Not only does Coates lack any meaningful facts or credible "experts" to support his indictment of horror comics, but he uses child actors a provide dramatization of what he thinks kids do to each other after reading horror comics as he prattles on about how reprehensible he thinks the comics are. The dramatization is so blatantly staged to fit Coates' view of what horror comics do to kids (think The Lord of the Flies in suburbia) that it's hard to believe that anyone other than Coates would take this episode seriously. Curiously, the episode was directed by Irvin Kershner, who would later go on to direct Empire Strikes Back.

(Then again, it has been argued by some that horror comics of the pre-CCA era weren't meant for kids in the first place. According to graphic designer Art Chantry, "The artists working this turf back then were virtually all war vets (it seems) with varying sorts of emotional damage (let’s be honest). The writers were virtually unknown haggard hacks and a few really f#$ked up madmen tossed in to the stew. Combine that with a forgotten generation of comic book professional hacks and an entire new generation of adult men who entered WW2 and the Korean war as children (and had to grow up way too fast) and you begin to see a crazy new market emerging. The truth was that these horror comics weren’t really made for 'kids' at all. They were made for new postwar damaged adults taking over the new modern world." Read Chantry's complete post about pre-CCA horror comics over at the Madame Pickwick Art Blog here.)

Trombetta's contextualization of the horror comics would be incomplete if he couldn't convey how popular they were before their government-mandated discontinuation. This point is driven home by the reprints of the horror comic covers from various titles between 1951 and 1954. There are dozens upon dozens of the covers on page after page in the book; I had no idea that there were so many horror comics published in such a short amount of time, which makes their subsequent disappearance from the newsstands after 1954 that much more stupefying to comprehend. If you only buy The Horror! for its reprints of rare comic art, you still won't be disappointed.

Where The Horror! stumbles badly is in its conclusion. Trombetta jumps from the mid-50s to the post-9/11 era in an attempt to make some larger point about censorship and how it functions in two different times in American history, but his argument falls flat due to its lack of substantial connection to the rest of the book. Had he paid more attention to how the horror genre and its fan culture had continued after 1954--and how many times that horror-related materials have been the subject of controversies both frenzied and fleeting in the years since then--he might have been able to build a firmer link between the 50s and now. For example, even though the CCA vanquished horror comics for a few years, it didn't stop Eerie Publications from publishing several horror anthology comic magazines from 1966 to 1981. Trombetta could have used this example to emphasize how futile the anti-comics effort ultimately was and how tragic it was for our government to violate the First Amendment for the sake of appeasing momentary hysteria.

Overall, The Horror! The Horror!: Comic Books the Government Didn't Want You to Read! is a book I would recommend to any horror fan who has a fervid appreciation of macabre visual art (such as horror VHS covers from the 80s and horror special effects work by artists such as Tom Savini, Rob Bottin and Rick Baker) and would like to learn more about the frequently forgotten golden age of horror comics.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)